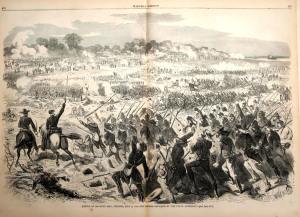

Today marks the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Malvern Hill, which was fought on July 1st, 1862, outside of Richmond, Virginia. Although a tactical victory for Union forces, this conflict, the final in a series of battles known as the Seven Days’, this battle marked an end to General George B. McClellan’s first time in command of the Army of the Potomac. It also marked the rise of General Robert E. Lee, and the Army of Northern Virginia, as a forced to be reckoned with in the Eastern Theater of the war. Here, we shall look at this battle, and its effect on the war.

The Battle of Malvern Hill was the culmination of the infamous Peninsula Campaign, which began in March of 1862, when Union General George B. McClellan led the Army of the Potomac from the Virginia Peninsula, in an attempt to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. Although a cautious man, “Little Mac,” as his soldiers affectionately called him, was almost successful, bringing his men to within a few short miles of the city. But it was mainly because McClellan faced a similarly cautious general in the form of Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. But all of that changed on May 31st, 1862, when Johnston was severely wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. In his place, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed his military adviser, General Robert E. Lee, to command the Confederate army in the field. It was a decision that Johnston himself credited as a great moment for the Southern cause.[1]

Lee wasted no time in preparing a campaign against McClellan. He sent one of his best cavalry officers, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, on a reconnaissance ride that would eventually complete an entire circuit around the Union army between June 12th and June 16th. From the information Stuart gathered, Lee chose to attack the enemy. This decision would culminate in what would become known as the Seven Days’ Battles, of which Malvern Hill would be the final conflict in a series of six engagements fought over several days. In assaults at Oak Grove, Mechanicsville, Gaines’ Mill, Savage Station and Glendale, Lee would time and time again attempt to drive Union forces from strong defenses. And with the exception of Gaines’ Mill, Lee would be defeated at every chance. This frustrated Lee, who wanted to deal a complete blow to his enemy. However, it did have an effect on the mind of his opponent. McClellan feared that he was outnumbered, and even though he won several of the engagements during the Seven Days’, he continued to pull his troops back, fearing that his men might be destroyed, and with it his reputation.[2]

After several failures to defeat the enemy, and drive them from their positions, Lee still hoped to achieve success. But this time, the Federals had set up a defensive position on Malvern Hill, their strongest one yet. “One hundred and fifty feet high and flanked by deep ravines a mile apart, Malvern Hill would have to be attacked frontally and uphill across open fields. Four Union divisions and 100 guns covered this front with four additional divisions and 150 guns in reserve. Unless these troops were utterly demoralized, it seemed suicidal to attack them.”[3] Yet lee chose to do so, with many signs leading him to believe the enemy was demoralized. That, along with his frustration at continual failure, led him to attack “those people” yet again. Longstreet, usually against this type of assault, shared his commanding officer’s sentiments.[4]

The attack was planned for the morning of July 1st. That morning, “Longstreet found two elevated positions north of Malvern Hill from which he thought artillery might soften up Union defenses for an infantry assault. Lee ordered artillery to concentrate on the two knolls. But staff work broke down again; only some of the cannoneers got the message, and their weak fire was soon silenced by Union batteries. Lee nevertheless ordered the assault to go forward.”[5] Lee had once again hoped that artillery crossfire would silence enemy artillery, and once again, that hope was not realized. Despite this, the men were ordered to move forward. What followed was a series of piecemeal assaults. “Some intrepid souls actually stormed to the crest in the face of overwhelming fire; most were mowed down along the slope or fell to the ground, unwilling to advance farther, and made their way back when they thought it was safe.”[6]

For some of the Confederates, Malvern Hill would be their first time in battle. One of the units who would see the elephant for the first time was the 49th North Carolina, commanded by Colonel Stephen Ramseur, and part of Robert Ransom’s brigade. Having only trained for two months before being put into battle, Ramseur wrote to his brother about his misgivings before the fight. “I do not put much confidence in my men,” and said that they “look scared & anxious.”[7] But just as other Confederates would make their own states proud, the 49th NC would do well under fire. One of the men who wrote of his experiences in this fight was William A. Day, a private in Company I from Catawba County. Years after the war ended, he wrote of his experiences while serving with the 49th.

Of Malvern Hill, Day wrote a vivid description of his Company’s action:

We arrived in the vicinity in the evening and formed our line of battle in the woods near the clover field. We remained there till late in the evening. When the advance was made we moved out of the woods into the clover field, and were soon in full view of the hill. We moved rapidly across the field, keeping our lines in perfect order under terrible fire from the batteries on the hill. We could see our artillery retreating, lashing their horses. The fired was too hot for them, and they had lost so many men they had to fall back. When we reached the fence a staff officer was there sitting on his horse crying at the top of his voice: “Lord God Almighty double quick, they are cutting are men to pieces,” and kept on repeating those words. In crossing the fence and swamp our lines were broken and, moving on the foot of the hill where we were sheltered from the fire, we re-formed our line. In a few moments the command charge was given. We gave what the Yankees were pleased to call the “rebel yell,” and started at double quick up the hill, and were soon breasting the storm.

General Bob Ransom, with a white handkerchief around his cap, spurred his horse through the lines and dashing in front of the 49th Regiment, called out in a voice that could be plainly heard above the uproar of battle: “Come on boys, come on heroes, your General is in front” and kept cheering us until we had nearly reached the Crews house. He then turned and galloped down the line. We charged up to the Crews house within thirty feet of the batteries. Sergeant Frank Moody of company I was carrying the colors. They almost wrapped us in flames – we could go no further. We halted and fired round after round at the Yankee artillerymen, whose faces shined by the flash of their guns. Our firing seemed to make no impression on them. Our Colonel Ramseur was badly wounded, and passed the order down the line to lie down. This sheltered us from the fire, which passed over our heads. We lay upon the ground about five minutes, when orders were passed down the line to fall back in good order. The batteries by this time had slacked their fire. We moved back until we were under cover of the hill and re-formed our line.[8]

According to Day, Company I lost sixteen men killed, wounded or captured. Losses amongst the other companies in the regiment were high as well.[9] Overall, Lee’s failure at Malvern Hill cost the Confederates over 5,600 men, while Union losses amounted to around 2,100. D.H. Hill called the battle murder, and not war.[10] Once again, Lee had failed to dislodge Union troops from their defensive positions. And yet, McClellan, fearing himself outnumbered, once again ordered his men to fall back. In August, after spending the entire month of July with their backs against the James River, Lincoln ordered the men to withdraw from the Peninsula to help with events taking place in Northern Virginia.

The Seven Days’ battles, which culminated with Malvern Hill, had been extremely costly for the Confederacy. In the six battles that took place between June 25th and July 1st, the Army of Northern Virginia had only won one of the engagements, and lost over 20,000 men in the process, while Union forces lost nearly 16,000 men. However, despite Confederate failures, McClellan’s cautiousness forced him to continue falling back, despite outnumbering his forces. When he and his men were pulled from the Peninsula in August, Lee and the Confederates had a tactical victory. With this, Lee began to plan an offensive against the Union Army of Virginia, commanded by John Pope, leading to the Battle of Second Manassas at the end of August, briefly freeing Virginia from Union troops, and leading Lee to plan his first invasion of the North. With the Seven Days, the legend of Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia was forged.

Works Cited

Day, William A. A True History of Company I, 49th Regiment, North Carolina Troops, in the Great Civil War, Between the North and South. Newton, N.C.: Enterprise Job Office, 1893.

“Dod Ramseur to Brother, 5 June 1862.” Stephen D. Ramseur Papers. Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008.

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

[1] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 461-462.

[2] McPherson, 463-469.

[3] McPherson, 469.

[4] McPherson, 469.

[5] McPherson, 470.

[6] Joseph T. Glatthaar, General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse (New York: Free Press, 2008), 139-140.

[7] “Dod Ramseur to Brother, 5 June 1862,” Stephen D. Ramseur Papers (Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill).

[8] William A. Day, A True History of Company I, 49th Regiment, North Carolina Troops, in the Great Civil War Between the North and South (Newton, N.C.: Free Enterprise Job Office, 1893), 20-21.

[9] Day, 21-22.

[10] Glatthaar, 140.